As graduate students in the Johns Hopkins Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design program, Noah Yang and Shayan Roychoudhury spend their days crafting solutions to complicated health problems. But when the unprecedented threat of COVID-19 spread across the globe, Yang, 24, and Roychoudhury, 22, had to leave campus, their research projects put on hold.

Three weeks ago, they came up with an idea to help fight against the most massive health threat of our lifetime. CBID had organized design challenges in the past to identify solutions to Ebola and Zika, along with humanitarian issues in the Middle East. Why not create a virtual event to solicit ideas from around the world to fight the novel coronavirus? “We were just really driven to do something,” Roychoudhury says. “With all the time we have with social isolation, it was the perfect opportunity for us to work on this.”

The two pitched the concept of the COVID-19 Virtual Design Challenge to Youseph Yazdi, CBID’s executive director, who was eager to support the plan. The CBID program is focused on creating scalable, marketable solutions to complex issues, and its pragmatism is well-suited to the urgency of the pandemic. “The main metric of success for CBID is impact,” Yazdi says. “What is the impact our students are having on the world, and what is the impact our ideas are having?”

Working from their respective homes, Yang, of Edmonton, Canada, and Roychoudhury, of Madison, Connecticut, assembled a leadership team and started spreading the news about the five-day design challenge. Participants would be able to access the most up-to-date research about the virus, learn about the challenges facing health care workers and public health officials, and connect with mentors as they hammered out their ideas. Within days of announcing the challenge, 515 teams composed of 2,300 participants from 25 countries had applied. Owing to the extraordinary response, the organizers closed registration early and selected 235 teams to continue with the challenge.

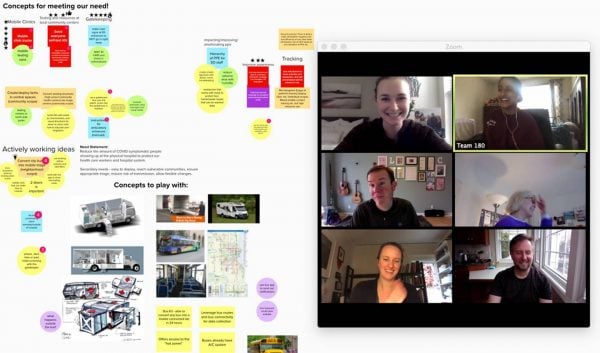

The teams focused on three main problems: how to educate the public about COVID-19, how to stop the spread of the virus, and how to combat shortfalls of necessary supplies and equipment, including surgical masks, protective gear, and ventilators. The challenge kicked off with a three-hour virtual seminar on Thursday, March 24. Teams refined their ideas from Friday through Sunday, interviewing health care workers about their needs, collaborating over Zoom videoconferencing software, and in many cases crafting prototypes in their homes.

“We were pretty much on Zoom from Thursday night through Monday,” says Ruchita Kothari, 23, A&S ’19. Kothari, who is currently enrolled in an MD/PhD program at the School of Medicine, had assembled a team of current and former classmates to come up with a solution to ease crowding in hospitals. They conceived of an app that enables paramedics to triage the symptoms of a suspected COVID-19 patient and then matches the patient to the hospital best able to meet their needs.

On Monday, the teams shared slideshows with panelists from CBID, again by video chat. Several groups focused on the shortage in N95 masks, one of the most effective tools in preventing the inhalation of viral particles. The masks are designed to be disposable, but, because of extreme shortages, many health care workers have been instructed to reuse them. This is problematic because masks can become contaminated or grow soggy when worn for many hours. Several teams came up with ways to disinfect the mask, using, for example, a rotating UV light stand or a portable UV device. Another team created a disposable cover for the mask out of surgical drapes, a material abundant in hospitals. Yet another conceived of slim pouches of table salt that could be slipped into N95 masks to absorb excess moisture.

Among teams focused on solutions not related to masks, one hopes to combat misinformation about COVID-19 by creating a web browser extension that flags inaccurate information or an app for health care workers that aggregates the latest research. Another turned their attention to the millions of people who live in refugee camps—and who are especially vulnerable to the virus since they live in close quarters and lack adequate soap and water to wash their hands. The team created a simple device that synthesizes bleach by jolting salt and water with an electric current powered by solar panels. The bleach could then be diluted and used to sanitize hands and surfaces.

Presenter Helen Xun, 27, a Hopkins medical student from Portland, Oregon, had already been working in the field of translational medicine. Currently on a leave of absence from med school, she is creating a startup to rapidly 3D print crucial medical supplies. For the hackathon, Xun’s team took an idea already in practice in some hospitals—sharing ventilators—and came up with a way to make it safer.

“We’re developing a ventilator splitter that enables each patient to get a more tailored therapy,” she says. The device, which they’re calling Vent-Lock, enables health care workers to see how much oxygen each patient is receiving and to adjust oxygen levels as needed for each patient. The team also created a filter for the splitter that prevents cross-contamination. Both the adjustable ventilator splitter and the filter can be printed on any 3D printer, Xun says. Vent-Lock has already received a $25,000 grant from the Office of the Provost, and work is underway to create a prototype for testing.

Johns Hopkins committed $225,000 to bring ideas from the COVID-19 design challenge to fruition, says Yazdi, CBID’s director. All the ideas will be posted to an open source website hosted by CBID, allowing others to experiment with or improve upon them. Yazdi expects at least some of the concepts will become a reality, just as the Ebola challenge led to production of a protective suit by DuPont. This time, of course, the timeline is compressed. “In this crisis, we’re looking for things we can use in the next two weeks,” he says.