Bailey Surtees always wanted to become an inventor. Growing up, she spent her time designing and building—Erector sets, small engineering projects, and other things.

But while Surtees worked on her inventions, she also dealt with health complications that often kept her out of school. When she was 12, Surtees—who is deaf in her left ear—had an operation that involved reconstructive work. The procedure fascinated her. Her doctor, noticing her interest, explained the surgery and introduced her to the larger world of bioengineering.

“He was the one who made me realize you can engineer with the human body,” Surtees says. “You could take this beautiful, natural thing, and you could add man’s creativity to it and create something even cooler.”

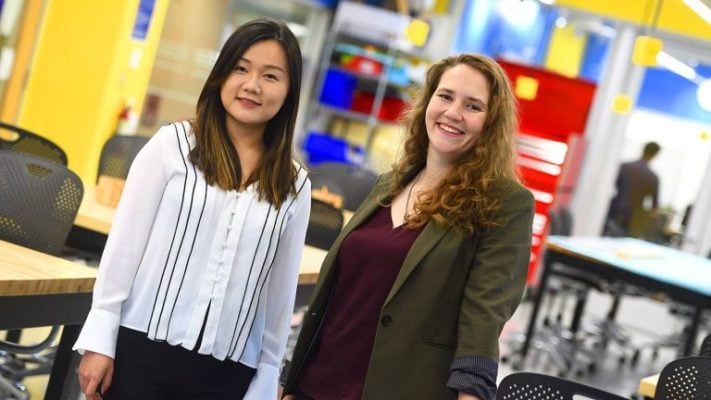

Now a research assistant in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Johns Hopkins University, Surtees is using her passion for biomedical technology to lead a team working to increase the survival rate of breast cancer patients in South Africa.

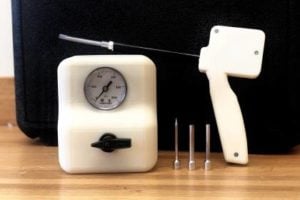

Kubanda—named for the Zulu word for cold—has developed a low-cost tissue-freezing device that can be used in low-resource settings where more conventional treatments are difficult to access. The team formed in 2016, and Surtees, then a junior, served as technical lead. At the beginning, it wasn’t a medical tech startup, but an undergraduate design team formed to improve access to breast cancer diagnostics and therapeutics in South Africa.

During the group’s two trips to South Africa, Surtees and the team visited hospitals in Johannesburg, Cape Town, and more rural areas to learn about existing treatments and needs. Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation are often too expensive and impractical for many patients, contributing to a high mortality rate for those who are diagnosed.